A Voice in Motion: Protecting the Dignity of Blind Riders in Angola's E‑Hailing Future

A Voice in Motion: Protecting the Dignity of Blind Riders in Angola's E‑Hailing Future

By Ayanda Holo

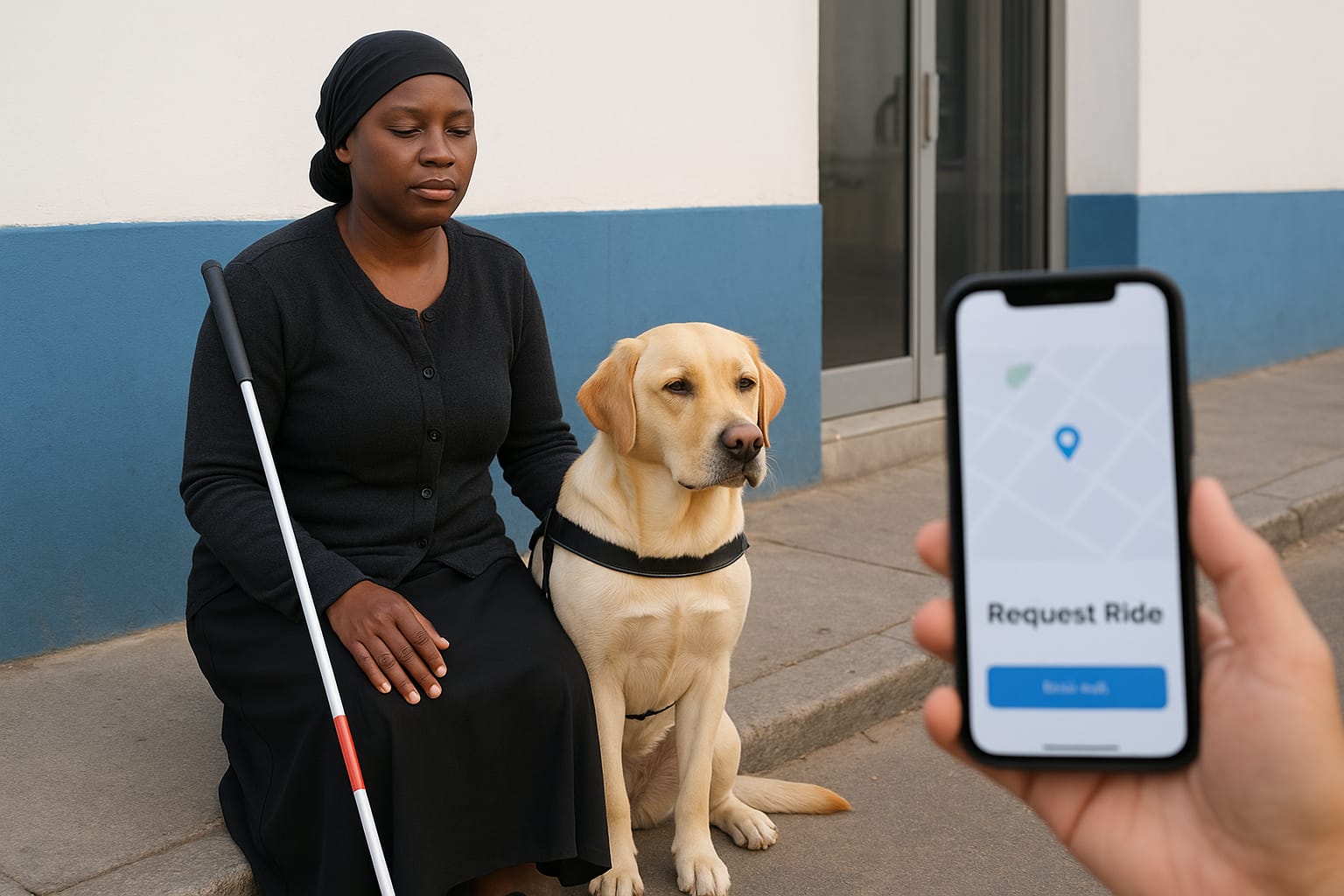

Maria, a blind woman in Johannesburg,had every reason to believe her e‑hail journey would be simple. She tapped "Request Ride" on her phone, received the driver's confirmation, and waited on the curb with her guide dog. But the moment the driver pulled up and saw the Labrador at her side, the booking was abruptly cancelled.

"It's like you disappear,"she told me later. The promise of what this technology is supposed to offer —independence, safety, dignity — was shattered in the instant a driver chose prejudice over policy. What followed for Maria was not just the inconvenience of arranging another ride. It was the erosion of trust in a service designed to empower those who rely on it most.

Her story is echoed thousands of timesover in cities around the world. In Cape Town, refusals have become so common that the South African Guide Dogs Association has taken Uber's Dutch parent company to court, arguing that accessibility statements are meaningless without active enforcement. In Australia, a visually impaired woman kept count:thirty-two refusals in three years, drivers waving her away to book on"Uber Pet," oblivious or indifferent to the law that makes discrimination against guide dogs a criminal offence. In the United Kingdom,blind passengers have taken to prosecuting drivers under the Equality Act, not because they relish the courtroom, but because their legal right to equal service has been so routinely violated. In Canada, only after intense advocacy did the country's largest blindness organisation succeed in making driver disability-awareness training mandatory on major platforms. Tokyo's taxi industry, aided by government support, has demonstrated what inclusive technology can achieve, with taxi apps seamlessly integrating accessibility features and compliance monitoring.

At the root of these examples lies the same reality: when the right to mobility for people who are blind is left to chance, the consequences are uniquely harmful. It is not simply about missed appointments or delayed plans. Every denial leaves a mark — on confidence,independence, and dignity.

Angola now stands at the edge of the same precipice. The country's e‑hailing market, still in its early stages, is expanding rapidly through global players like Yango and smaller local operators in Luanda, Benguela, and other cities. For Angola's estimated 160,000 residents living with visual impairments, these services should offer the chance for greater independence. Instead, without deliberate preparation, they risk reproducing the same discriminatory habits seen elsewhere.

The legal foundation already exists.Angola's Law No. 10/16 on the Protection of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities explicitly prohibits discrimination in public and private transportation. However, legislation and lived reality are two very different things, and so far, private app-based transportation has neither specific guidelines nor consistent enforcement when it comes to riders with guide dogs.In recent discussions with advocacy groups in Luanda, several blind residents admitted they avoid app-based rides altogether. Stories surfaced of friends left waiting for over an hour as repeated driver cancellations forced them to abandon errands. Others spoke of resorting to informal, unsafe means of transport to get to routine medical appointments because, as one man put it,"you never know if the driver will agree to take you."

This uncertainty carries more than emotional weight. For many visually impaired passengers, e‑hailing is not a convenience; it is a bridge to essential care — to clinics, pharmacies,hospitals. Being refused a ride does not just waste time; it also wastes emotional energy. It can mean missing a chemotherapy session, delaying a diagnosis, or going without vital medication for another day.

Angola need not accept this as an inevitable cost of progress. The mistakes made elsewhere — from Canada to Australia — offer lessons that can be applied now, while the market is still inits early stages of development. Change begins with the recognition that accessibility cannot be an afterthought. Platforms like Yango do require every driver to complete meaningful, recurring accessibility training. This is done to be more than a perfunctory checklist of legal obligations, but an immersive process that uses the voices and experiences of blind riders themselves to convey the stakes.

Technology can help close the gap between policy and practice. An in-app feature that allows passengers to note they are travelling with a guide dog discreetly could dramatically reduce the element of chance in such journeys. This notification should appear on drivers'screens long before they arrive, alongside an unambiguous reminder that refusing service is not only unacceptable but unlawful. Cancellations of flagged rides should be tracked, investigated, and acted upon, with repeat offenders facing suspension or removal from the platform.

Transparency will ultimately decide whether these measures have meaning. Publishing anonymous quarterly reports that track accessibility requests, completion rates, and complaint resolution times would keep the issue visible to both the public and regulators. And it would send an important signal: this is not charity work; it is building a transport system that values every passenger equally.

The moral argument is clear, but so is the economic one. Studies across Africa suggest that approximately one in ten urban residents lives with a disability. For Angola's e‑hailing firms like Yango, providing truly accessible service could translate into tens of thousands of additional fares each month. It would also enhance brand loyalty and strengthen bids for future government transport partnerships.

By acting now, Angola has the opportunity to lead where others have stumbled. An inclusive e‑hailing sector could become a model for the region, proving that emerging markets are capable of marrying technological innovation with equity and foresight. Ultimately, the success of Angola's transport revolution will not be measured by the number of rides booked, but by whether those rides arrive for everyone.

A blind passenger waiting outside a clinic in Luanda with her guide dog should not have to wonder if the ride she ordered will come. She should know it will — without hesitation, without delay,without prejudice. That is the promise of e‑hailing in its most valid form. And it is within Angola's grasp to keep it.